Benel Lagua l November 29, 2024 l The Manila Times

THE late Charlie Munger said, “If you have a dumb incentive system, you get dumb outcomes.” Bartleby of The Economist cites Stephen Meier of Columbia Business School, who argued in the book “The Employee Advantage,” that people are motivated by many other things than just monetary rewards. Rewarding people for doing things they would do anyway can easily backfire.

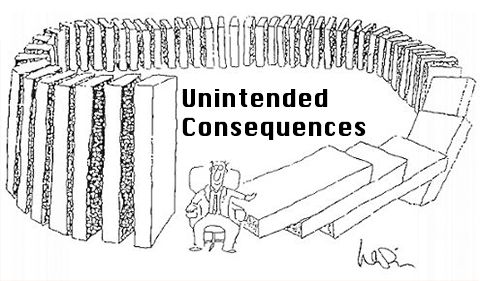

The idea behind rewards or penalty systems is to align individual actions with broader goals. However, poorly designed incentive systems often lead to unintended consequences that undermine their effectiveness and create additional challenges. Understanding these dynamics is critical for designing systems that achieve their intended purpose while minimizing negative outcomes.

One common unintended consequence of incentive systems is “gaming the system,” where individuals exploit loopholes to achieve rewards without fulfilling the true objectives. For example, in sales environments, employees may manipulate figures or employ aggressive tactics to meet targets, prioritizing short-term gains over customer trust and satisfaction. Similarly, in educational settings, teachers evaluated on student test scores may focus exclusively on test preparation, neglecting broader learning objectives. This behavior reflects a misalignment between the incentive metrics and the system’s overall goals.

A good example is the mandated lending for small and medium enterprises, which penalized banks if they did not lend the required 10 percentage quotas for small businesses. Critics claimed that the law was a failure, but a close study shows it was the penalty imposed by regulators that appeared to be the culprit. The penalty was a uniform amount of P500,000, regardless of bank scale. As a result, many banks, especially the big ones, have not been compliant and just opted to pay the penalties instead of assuming the risk of small business lending.

Another significant issue is the tendency of incentives to encourage a short-term focus. When rewards are tied to immediate results, long-term planning and sustainability often suffer. Corporate executives, for instance, may prioritize quarterly profits to meet performance targets, even at the expense of long-term growth or ethical considerations. This short-termism can lead to decisions that benefit individuals at the moment but harm organizations or society in the future.

Incentives can also inadvertently emphasize quantity over quality. When performance metrics are based on output, individuals may prioritize speed or volume over the caliber of their work. This phenomenon is prevalent in industries ranging from manufacturing to education, where workers or institutions prioritize hitting numerical targets without ensuring the quality of outcomes.

David Atkin of the Massachusetts Institute for Technology found that many football manufacturers in Sialkot, Pakistan were slow to adopt a technology that reduced the amount of synthetic leather wasted in production. The reason was the piece-work incentive scheme, where workers were paid by the number of balls produced. The workers did not want to waste time on learning a new technique.

A more subtle consequence of external incentives is the erosion of intrinsic motivation. When individuals are rewarded for tasks that they previously found inherently satisfying, their internal drive to perform those tasks can diminish. For example, students who are repeatedly rewarded with grades or prizes may lose interest in learning for its own sake. Similarly, employees motivated solely by bonuses may disengage from tasks not tied to immediate rewards, reducing their overall commitment to the organization.

Some incentive systems inadvertently encourage harmful or counterproductive behaviors, a phenomenon known as “perverse incentives.” A historical example is the “cobra effect” in colonial India, where authorities offered bounties for dead cobras to reduce their population. Instead, individuals began breeding cobras to claim the rewards, exacerbating the problem. Similar dynamics can occur in the modern context, such as health care providers overprescribing treatments to meet financial incentives, or ordering unnecessary tests to maximize utilization of hospital equipment, potentially endangering patient health.

To mitigate these unintended consequences, incentive systems must be thoughtfully designed and continuously monitored. Aligning incentives with the broader goals of the system is essential. For instance, incorporating holistic metrics that balance qualitative and quantitative measures can reduce the likelihood of gaming the system or overemphasizing the significance of narrow outcomes. Encouraging transparency and fostering long-term thinking are also critical, as they discourage manipulation and promote sustainable behaviors.

While incentive systems are effective tools for motivating behavior, their design requires careful consideration to avoid unintended consequences. By aligning incentives with the desired outcomes, incorporating comprehensive evaluation metrics and maintaining adaptability, organizations and policymakers can create systems that drive meaningful lasting change.

*** Benel Dela Paz Lagua was previously EVP and chief development officer at the Development Bank of the Philippines. He is an active Finex member and an advocate of risk-based lending for SMEs. Today, he is an independent director in a number of progressive banks and some NGOs. The views expressed herein are his own and do not necessarily reflect the opinion of his office or of Finex. Photo from Pinterest.