Benel Lagua l July 26, 2024 l The Manila Times

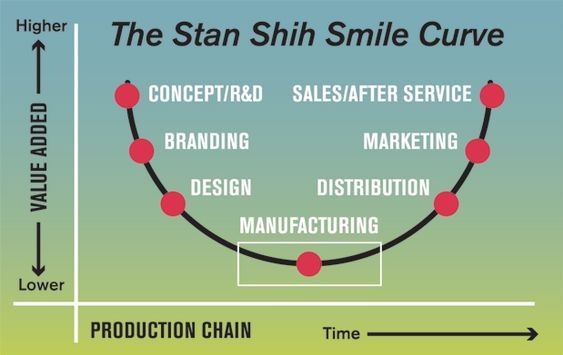

THE smile curve is a graphical depiction of how value-added varies across the different stages of bringing a product on to the market in an information technology (IT)-related manufacturing industry. This was first proposed by Stan Shih, founder of Taiwanese computer maker Acer, in 1992.

Value-added in a manufacturing process rises faster in the first and third parts of making a product than in the second stage. The first part is preproduction, which includes research and development, design and innovation, all of which are high value-added due to the intellectual property and specialized skills involved. The second stage is production or the actual manufacturing of the product, often outsourced to countries with lower labor costs. The third is postproduction, which encompasses marketing, branding, sales and after-sales services, adding significant value due to branding and customer relationship management. With value-added on the y-axis and the value chain stages represented on the x-axis, the resulting curve appears like the shape of a smile.

Acer used this concept to reorient itself from simple manufacturing. It invested heavily in research and development to develop innovative technology and positioned itself as a global marketer of branded PC-related products and services. As illustration, The Economist cited Apple which does not produce any of its iPhone itself, but focuses on its design, distribution and brand rental. Apple has a market capitalization of $3 trillion while Foxconn, which manufactures 70 percent of the actual iPhone, is worth $91 billion.

Understanding the smile curve provides insights to where companies and countries could concentrate to optimize value-added contributions. In general, developed countries focus on the high value-added slope of the smile curve, while developing countries have been contained to the low level value-added segment of manufacturing.

The Economist recently published a feature on service exports entitled “Virtual Everything.” The interested Filipino reader will find the opening paragraphs of the article educational and inspiring.

“In April, a New York fried chicken shop went viral. It was not the food at Sansan Chicken East Village that captured the world’s imagination, but the service. Diners found an assistant from the Philippines running the tills via video link.”

“The service is provided by Happy Cashier, which connects American firms with Filipino workers. Chi Zhang set up the business after his restaurant failed during the Covid-19 pandemic. He says that overseas workers also answer phone calls and monitor security-camera footage — doing so at a fraction of the cost of locals.”

If developing countries want to take advantage of the high slopes of the smile curve, they must develop a highly skilled and knowledgeable workforce, and harness the potential of service exports. The case is compounded with manufacturing now becoming more capital intensive and with robots emerging as the new factory workers.

The Philippines has seen substantial growth in its service sector over the past few decades. This growth can be attributed to several factors, including a young, educated workforce, strong English language skills and strategic government policies. Key segments within the service sector include business process outsourcing (BPO), IT and tourism.

The BPO industry is a cornerstone of the Philippine economy, contributing significantly to gross domestic product (GDP) and employment. The IT service sector in the Philippines has also experienced robust growth. This includes software development, IT support and digital services. Tourism is another vital component of the Philippine service sector. The country’s rich cultural heritage, natural beauty and warm hospitality attract millions of tourists.

The less techy category of “business- and trade-related services,” which covers fields like accounting and human resources, is where the Philippines appears to be making a mark. The same feature of The Economist shows the Philippines ranking next only to Estonia with such exports accounting for over 5 percent of GDP. The other categories like IT and telecoms, as well as health tourism, remain a fertile field for expansion.

The growth of the Philippine service sector illustrates how strategic positioning within the value chain is needed to drive economic growth. Some studies show that the service sector input contribution from the Philippines involves low productivity service inputs into intermediate good. Contrast this to the service-sector inputs from say, the USA which involves high productivity service inputs such as marketing, design and innovation service.

How can we move up the value chain? Per the World Bank, the Philippines is not fully harnessing its human capital potential given the country’s Human Capital Index of 0.52 in 2020. This implies that an adult can only achieve just over half of his/her potential.

The country must pay close attention to human capital, the knowledge, skills and health that people accumulate over their lives. Our government will have to invest heavily and support higher education. The internet infrastructure must improve to take advantage of international connectivity which makes various kinds of outsourcing and digital commerce viable. Remote work can also prosper under these circumstances. Continued focus on enhancing service quality, building strong customer relationships and promoting innovation will be crucial.

*** Benel de la Paz Lagua was previously executive vice president and chief development officer at the Development Bank of the Philippines. He is an active Finex member and an advocate of risk-based lending for SMEs. Today, he is an independent director in progressive banks and in some NGOs. The views expressed herein are his own and do not necessarily reflect the opinion of his office as well as Finex. Photo from Pinterest.